Interviewed by Betty Blayton

Can you start by telling us when and where you were born?

I was born on December 22, 1948, in Birmingham, Alabama, to Louise Bennett and William H. Burgess Jr. Louise Bennett Burgess was an artist and educator, and she gave me my first instruction with respect to art. I was an only child of an only child (my father). My mother came from a large family. My mother's family wasn't very well off, but my father's family was, so I grew up in a household of a Democratic mother and a Republican father. My father had his own businesses and because the Republican Party was the party that freed the slaves he pretty much considered himself Republican. Both my parents went to Tuskegee. My mother graduated from Alabama A & M and then got her first master's degree at Tuskegee.

That's the start. No Burgess male since slavery has worked for anybody else. They've always had their own businesses so an entrepreneurial streak has been in the family from the very beginning and it coincides with the art part, as well.

I first started drawing on rainy days. My mother had wanted to be a professional artist and had applied to the Chicago Art Institute, but she and my father got together the summer before, so she never got to go to Chicago.

I grew up in Birmingham and went to public schools there. My job was to be the best in my class according to my father. He was a taskmaster. He was the one who made sure that I made good grades. My mother was a principal, but she never bothered me about my study habits. My father was meticulous. He taught me the timetables and how to write my name. I was never good enough unless I had all A's. I came home with A's in every subject except for one B in physical education, and he asked me, "You mean you can't play?" In the long run his attitude was a good one because it really taught me what it meant to achieve something. When we would sit down for dinner at night the first question out of his mouth was, "What did you do today?" I had to give him a daily detailed report about what went on in school; what I did, who said what, who did what.

Were there any challenges in Birmingham in terms of race? Were you conscious of the fact that you were living in a segregated place?

I was conscious of it, but because we did fairly well I never had to ride in the back of the bus. I never had anybody speak to me in a derogatory way. I was a pallbearer for three of the four little girls that were killed in Sixteenth Street Baptist Church. I will never forget the Sunday it happened. It was September 15th, 1963.

Was that your church?

No. Sixteenth Street Baptist Church was on the corner of Sixteenth Street and Sixth Avenue. My church, St. Paul United Methodist, was on Fifteenth Street and Sixth Avenue. The day that the bomb went off I was in Sunday school. I was president of my Sunday school class and was bringing the collection plate downstairs from the classes to be counted. The building shook when the bomb went off and literally the sky went black because of all of the dust. It was a massive explosion and shook our church so badly that the foundation had to be resettled.

I was a friend of three of the girls and that's why I was a pallbearer at three of the funerals. One of my father's friends from Tuskegee was Carol Robinson's mother, Alpha Bliss Robinson. She asked my father if he had seen Carol. My father then turned to me and asked me if I had seen Carol. I hadn't seen her, but my first thought was that maybe I had because I saw so many people I knew running out of the church all bloody from cuts all over them, so I said that I thought I had seen her. Later, we found out that she had been killed in the bomb blast. My father accused me of lying for saying that I thought I had seen her. He told me that I needed to apologize to Mrs. Robinson. Just at that time she called our house and spoke to my parents. She told them she was glad that I had said that I thought I had seen Carol because it allowed her to get home, and she was with her family when she got the news. As a result, she told my parents she wanted me to be a pallbearer at Carol's funeral, which lead the other friends' parents to ask me as well.

In Birmingham it was only when these upper middle-class girls were killed that the entire black community became galvanized and brought everyone together. It made everybody realize that no matter who you were and how much money you had; you would always be a target.

When did you first become really interested in art?

I went to A.H. Parker High School in Smithfield, the north section of Birmingham, when I was twelve, and in the ninth grade I won "Best in Show" at the Annual Art Contest. I did an abstract painting and it was the only abstract painting in the competition. It set the tone for how I viewed art and still view art today. I see that our art stems from our African history as a people, coming from the crafts we created during slavery in this country and in the decorative arts we did in the South. Those creative attributes that we exhibited, developed into a form of painting and sculpture in the more traditional forms, more figurative and natural depictions versus abstract forms. My decision to do an abstract form of art for the exhibit came after I had studied a little a bit about art and realized that after World War II, abstract expressionism had became the major art form; and it was this form that had eclipsed Paris for New York City to be the center of the international art scene, and I wanted to create something different.

In the ninth grade you were actually aware of that?

Yes. My mother had told me about all the different periods of art. She started off with the Seven Wonders of the World. From the World Book Encyclopedia collection we had on the library shelves she would show me where all these Wonders were. She told me how art, history and culture all went together and that art was really a depiction of history, so it was not something to think of as being frivolous or secondary. That was my first experience with art and my first kind of reward from engaging in art.

For high school you went to Philips Exeter Academy. Can you tell us how and why you went there?

I went to Phillips Exeter Academy because I was a National Merit Scholar, after high school. This school was in Exeter, New Hampshire. Abraham Lincoln's sons went there. All of the presidents after Lincoln either went to Exeter in Andover, Massachusetts, or Exeter in Exeter, New Hampshire. One of my classmates was Scott Carpenter, son of one of the famous astronauts.

Corresponding with art in high school, I was also heavily into science. I was really influenced by Sputnik in 1957. I got a dog for my birthday and named her Missile, but eventually changed it to Missy. I did science projects every year. From the ninth through twelfth grades I won Best in Science Fair Awards at my high school, for my county, and for my state. Then I was recognized by the National Science Foundation and was able to work in a laboratory at the University of Alabama, which was segregated at the time. I did a study on the effects of taking thalidomide during pregnancy. I was fourteen at the time. I had read in an encyclopedia how to make an incubator. I made one and would hatch chickens in it. I would time it so that they would hatch around Easter and Thanksgiving, and I would sell the baby chicks, turkeys, and eggs to my neighbors and friends. From that I used the eggs in the thalidomide experiments I conducted. I injected the eggs withthalidomide, and I showed that in the gestation of a chicken, which is only twenty-one days, the thalidomide caused birth defects. I got a scholarship because of that and got a letter from Dr. Benjamin Mays, President of Morehouse College, asking me to come to Morehouse after my sophomore year. My dad said I was too young to go to college at fifteen, but I did go to college when I was sixteen. I went to Exeter first, and they wanted me to stay an additional year to go on to Harvard or another Ivy League school, but I didn't necessarily want to do that.

Was this before the effects of thalidomide were known?

It was simultaneously known, but scientists were not sure what was causing the defects. Women were taking other drugs during pregnancy too, so no one was quite sure what was actually causing these deformities.

Where did you go to college?

After the summer at Exeter, I got scholarships to go to any college that I wanted to go to in the United States, from the National Merit Scholar Program and the National Science Foundation. I chose Lake Forest College in Lake Forest, Illinois. I looked at the map, took a compass, and chose a place that was one thousand miles from Birmingham. That was Chicago, due north. I looked for colleges that were small, liberal arts colleges. Lake Forest was twenty miles north of Chicago, so I chose that. My father wanted me to go to Tuskegee because he had gone there, but because of the science project scholarships I was not limited as to where I could go to college, and he finally gave in to Lake Forest after visiting it with me.

At what point did you decide to major in art history?

It was a combination of things. My father had a number of businesses that he inherited from his father. He had an interstate trucking business, two poolrooms, and hotel businesses. One of the things about segregation was it required that you had to have your own resources. My father also had a nursing home business and wanted me to become a doctor and come back and run his nursing home business. I was tired of my father's instructions, so when the college gave me the opportunity to go to Florence, Italy for junior year I jumped at it. My girlfriend at the time had already been to Europe, and she encouraged me to go also. She worked as a waitress, and I worked as a bartender and waiter at local country clubs. We pooled our money together and flew to Iceland first and then to Luxembourg. Then we travelled around on the Orient Express to Istanbul and then to Beirut and Cairo. Then we went down the Nile to Thebes and Luxor and came back through all of Greece, took the boat from there to Brindisi, and then to Florence by train to study there our junior year. That's how I got into art history. I loved studying the history of the Renaissance, Italian art and culture and came back and changed my major from pre-med to art history and my minor to American Civilization. I graduated from Lake Forest in 1969 at age twenty with a BA degree in art history. My same girlfriend was from New York, and she suggested that we move to New York after graduation. I didn't want to go back to Birmingham, because my father would have made me go to medical school. When I left Lake Forest I applied for medical school at Columbia Presbyterian, and I got in. That was a way to get my father off my back so I could get to New York.

We moved to New York on September 15, 1969 and I went to medical school for a semester. One day I went to the Metropolitan Museum of Art to take a break and was looking at an exhibition entitled "New York Painting and Sculpture 1940-1970." I was talking to myself about the art while standing next to a group of people. I said, "The person who put this exhibition together doesn't know anything about art." I didn't know the people next to me heard this, and I didn't know that the curator of the exhibition was one of those people, and he was the famous Henry Geldzahler. The people he was with were all donors to that exhibition. One of them said, "What do you mean by that?" I said, "For one thing, there are no women in this show and there are no black artists in this show." They turned to Geldzahlerand said, "Is this true?" and he said it was. He asked me what I was doing the next day, and I said that I had to go back to medical school at Columbia. He invited me to come to lunch so I went back for lunch the next day, and he offered me a job immediately. The job was a Chester A. Dale Fellowship to do curatorial research on the holdings of the twentieth-century art department. The Metropolitan used to have a law that any artist works that they bought had to be dead for seventy five years. Art by living artists could be donated to the museum, and they would accept it, but in order to buy the work they had to make sure this person was going to be famous before they bought the art, therefore the artist had to be dead. My assignment was to go through all the holdings of all the artwork within the twentieth-century art department and to catalogue all of the works they had in the collection. In doing so I found out that they only had work by four African Americans: two watercolors by Romare Bearden, one etching by Hale Woodruff and one drawing by Charles Alston. I convinced Henry Geldzahler that we needed to buy some more African American art. He asked me whom I would suggest, and I told him that Cordier & Ekstrom Gallery nearby on Madison Avenue was having an exhibition of Bearden at the time, and we could get a large work for only twenty thousand dollars. We went over and bought it. After that we bought other works by African American artists from his acquisition budget. Geldzahler got more interested and a lot of black artists started calling, so he began to have access to finding more works by other black artists. Because of my fellowship I met a lot of artists like Barnett Newman, Helen Frankenthaler, James Rosenquist, and Ken Noland. I never met Warhol but I remember that Henry often had Warhol coming in to the museum to show him new works from the Factory.

Do they still encourage artists to come in with their portfolios now?

They do and all of the curators have an opportunity to look at new artists work. One day I was there and Frank Stella came in with his work and the museum decided to use his "M" emblem suggestion for the Metropolitan's Centennial Exhibitions announcements that he created.

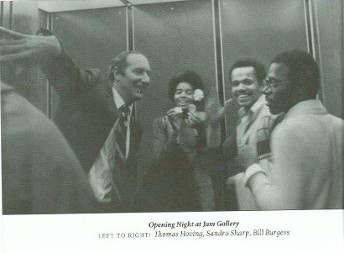

I was there during Thomas Hoving's tenure as director. He had a grand architectural style of directing. He was very instrumental in getting me interested in museum administration. He said in a letter to me that he viewed my abilities in museum administration in terms of what he thought I could do and what I would be capable of in expanding the outreach of the museum to audiences typically unfamiliar with frequenting museums. My Chester Dale Fellowship at the museum was only for six months and my curatorial assistantship to Henry Geldzahler ran for another six months of my first year there.

I came in 1970 and was able to buy a lot of work like the Van Der Zees from Reggie McGee. I bought my first Tanner etching from Grand Central Art Gallery, then on West Fifty-seventh Street. I happened to be there when they had gotten a letter from Jessie Tanner, Tanner's son who was still living in France. He was coming to New York, and I asked the gallery would he authenticate his father's unsigned etching that I had bought, and he did. As a result, I have a series of letters from when I began writing to Jessie Tanner that I've kept about how he viewed his father's work. Later when I went to the Studio Museum in Harlem where I was Director of Education, we were doing an exhibition on the work of Henry Tanner. At that time I used those letters for the catalogue I cowrote with the Hyde Collection of Connecticut, who co-curated the exhibition with the Studio Museum.

In my second year I moved to the position of Associate, High School Programs, in the Education Department of the Metropolitan. I advertised it in all of the regular news publications to attract public and private high school students interested in art history. I also had a course for adults, their parents and Dolores McCullough, who is here today, was one of my first adult students at the Met. She wrote a letter to Tom Hoving about how important it was for the museum to be more inclusive and to have programs geared to different audiences that traditionally had not been accustomed to going to the museum. Hoving gave me a copy of the letter, and I still have that letter.

How did you get to the Studio Museum?

It was through Edward [Ed] Spriggs, who was the executive director of the museum at the time. He had heard about my education programs at the Met. We got the Met to place some of their African art in different nontraditional places. We took an old movie theatre on Tremont Avenue in the Bronx and converted it into a museum of African art. From that I got the idea to create an arts in education consortium, called the Museums Collaborative to aid New York City arts organizations, museums, botanical gardens, zoos and environmental centers in collaborating on extending the boundaries of arts in education programming, city-wide. While I was Director of Education at the Studio Museum, one of the programs was the Sunday Afternoon Events. Danny Dawson, who is here today, was head of the Video and Film Workshops, and he held lectures on Blacks in cinema and the early pioneers in cinema on Sundays. We would also show films and stage dance and musical presentations, installations that depicted different art aspects, and political movements that were going on at the time.

That was during the time of the Black Power and Nationalist movements and the museum's main focus was to provide a center and outlet for African American awareness, representation, expression, and education in all art forms.

I had gotten tired of working at the Metropolitan behind closed doors and nobody really saw their many collections and work that I was doing. At the Met I conducted classes for high school students where I would take them into the Costume Institute and let them try on some of the famous fashions in the collections, like early Chanel suits and gowns of the Art Nouveau and Deco periods. When people ask me why I left the Met, it is because I didn't think that I was going to be able to do as much there as I could do at the Studio Museum in terms of art education and Afro American Art awareness. Also, I was offered more money to work at the Studio Museum than I was making at the Met. Museum salaries were notoriously low and still are.

The Studio Museum in Harlem was a turning point for me because it gave me a bigger platform. I ran the education department and in order to do the programs we needed to raise money. I wrote proposals, went out and raised money through the New York State Council on the Arts and the Department of Parks and Recreation. I paid stipends to some of the instructors for the additional time they were putting in for these educational programs we were presenting to and for the community we served. I hired some of the students I had at the Metropolitan as my interns so they would get the experience of working in a museum. Persons like Monica Freeman, who worked in film and video and have continued with her craft. Others like Valerie Maynard and Carol Byard, who ran the printmaking and sculpture workshops. Jim Phillips, now at Howard University Art Department, taught acrylic painting and murals.

That's how I met Betty Blayton. I met Betty because I knew that in order to get Ed Spriggs to let me use the money that I brought in for arts in education programs I needed a support group. Betty had been one of the original founders of the Studio Museum so I went to Betty. At that time she was Executive Director of the Children's Art Carnival in Harlem. She told me that I had to somehow go around to other people on the board and have them speak to Ed Spriggs about the importance of what I was trying to accomplish. I went to Russell Goings, Chairman of the Studio Museum's Board of Directors who ran the only black-owned brokerage and investment firm in New York City at the time on 125th Street, in the same building that now houses the current Studio Museum. I got Russell Goings and Ray Hulen, who was the treasurer of the board, to tell Ed Spriggs that I needed the money I raised to be used specifically for my education programs, not for other operational costs and expenses. He finally came around, and I was able to use the money to do the things that I just spoke about. I took a page from Betty's book of administration and that was to create a "Friends of the Education Department." I got a group of professional women who were interested in art education to be on my education committee. They included Janet Carter who was the wife of jazz bassist Ron Carter, and Elaine Dow, among others.

At the same time Camille Billops was in a three-person show with Al Fannon and Arthur Smith. Later on we had the Weusi artists and the first one-woman show of Elizabeth Catlett in New York. The other big show was the Henry O. Tanner in conjunction with the Hyde Collection. We also did a Palmer Hayden show. The two exhibits that I did the most work on from art historical and educational writing standpoints were the Tanner show and the Catlett shows.

The vice chancellor of city public schools, Dr. Edythe J. Gaines, heard about the arts in education programs we were doing at the Studio Museum. She was a very high-powered and respected educator in New York City public schools during the 1970's. She was the first black woman to become vice chancellor. She ran the Learning Cooperative, a "think tank" for innovative school curricula programming development, and she asked me to come to be Coordinator of Visual Art Resources for the New York City Board of Education. I was to write a compendium of available cultural resources in New York City. I went around to the environmental centers, the zoos, the botanical gardens, and museums and put together a compendium of all of their education programs that the Board of Ed could use in their curricula for arts education. From that we were able to influence the curriculum in the schools and bring more arts through education into the schools, which also grew out of the landmark pioneering work in art education that Betty Blayton was doing at the Carnival with Piaget and D'Amico of the Museum of Modern Art. All children can learn more and faster if learning is introduced through the arts. That concept was a concept that Edythe Gaines also saw and knew she could get by hiring me because I had learned the techniques from Betty. She hired me and Blanchette Rockefeller put me on the Rockefeller Brothers Foundation's Museum Administration and Arts in Education Board where I represented the New York City Board of Education and community based arts institutions.

Art during the seventies, more than any other time, was really segmented into traditional, white, mainstream art and "other art." The "other art" was black art, Hispanic art, and other ethnic arts. I always felt that it was wrong to say that Art done by an African American was "black art" and that was all there is to say about it. Art done by an African American is American Art, first and foremost. Black artists are American artists that happen to be black is my feeling about how they should be regarded and that's my feeling about this major subject when it was discussed then during that period, as well as today. At that time a lot of people felt that they should be known only as black artists and that being American was secondary; quite the contrary.

Who was saying that?

A lot of different people who were in the Arts at that time. From the beginning there were the traditional white art historians, critics and media, and later to due to Black Power, there were the Weusi Group and the AfriCobra Group who were all saying this. There were a lot of groups that wanted to be known for their reasons as black artists first. It was due, in combination of, first our being rejected by the traditional art establishment as being lesser, inferior, and then by our own groups who countered that our art was not ruled or dictated by white aesthetics or measures of institutionalized art and forms. I still maintain and have from the very beginning to this very day that art done by anyone in America is American Art and it should be judged fundamentally whether it is either good or bad and not on the basis of first and foremost the artist's ethnicity. The fact that he or she is African American is a secondary historical fact.

While at the Board of Education, I continued the development of the Museums Collaborative; I had started encouraging the sharing and borrowing of cultural resources and accessibility between institutions. I took the compendium that I had written and tried to make all of these museums, botanical gardens and zoos collaborate with one another programmatically. It is still going on today to some degree, but not to the degree that it was then because of all sorts of insurance and ownership issues.

Can you speak about the murals that were done in Harlem at that time?

At the Studio Museum we did murals in the neighborhood right around the museum. The Studio Museum was on 125th Street and in the streets bordering Fifth Avenue there were a lot of murals that we created in those vest pocket parks. Dingda McCannon, Jim Phillips, Ademola, Kay Brown, members of Weusi and Where We At were some of the artists working on those murals. Kay Brown started Where We At, and she was not only a political artist, but also a feminist. There were quite a few women artists who were working with Kay, like Dingda up at the Studio Museum at that time.

I think it's important to say that institutionally the Studio Museum was the first museum that was set up in this country that dealt with African American artists that were young practicing artists. The studio concept of having art as it is created being brought forth and presented to the community that it was a part of and served was a new concept in cultural institutional building. It was trying to make art more accessible to the community and also to give artists an opportunity and space to produce their art. The Studio Museum was unique in formulating and implementing that concept.

Were you there when they wanted to move the museum?

No, that was after I left. They wanted to move it to East Harlem where El Museo Del Barrio is now on Filth Avenue and East 103rd Street.

I wanted to talk about the concept of politicization of art and what it meant to the artists that were working at the time. Suffice it to say that none of the major museums have done to any large extinct what they need to do in terms of supporting and presenting the works of nonmajority artists. This is the third reincarnation of this kind for me, and I am now again on the board of the Metropolitan's multicultural audience development initiative. This is the third machination of something that is supposed to encourage larger attendance and audiences of minorities. They approach it from the wrong way each time. They don't put any money behind it. There is still that traditional idea that art is for the wealthy. We have come a long way in terms of the museums being more diverse in their collections and diverse in their employees, but not significantly so still in forty years.

Can you talk about your move to the Brooklyn Children's Museum?

The reason I went to the Brooklyn Children's Museum's MUSE is because I wanted to run the show. I was twenty-five years old and was making $20,000 a year. I started at the Metropolitan at $6,800 a year and graduated from that to $20,000. In five years. I had done very well. Vivian Browne, God bless her soul, asked me, "Have you got $5,000?" I said I did. She said, "There are two floors in my building for sale on West Broadway. They are $5,000 a floor." That was all the money I had. Instead I bought a Tanner etching for $2,000 and took the other $3,000 and bought about fifty signed Van Der Zee photographs.

Did you meet Van Der Zee often?

Yes. I paid light bills for Mr. Van Der Zee and bought him food. It's not that he couldn't afford things, but it was hard for him to get around with his age, weight and infirmities. He needed people to help him with things.

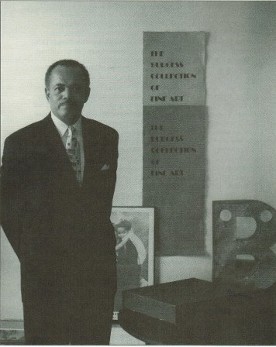

While I was at the Metropolitan, the Studio Museum, and at the Board of Education, I had an art gallery in my apartment at 530 Riverside Drive and my first exhibition was of Mr. Van Der Zee's photographs. Then I did an exhibition in 1976 and it centered on Romare Bearden and Norman Lewis. It was the only time I didn't get along with Norman and it was about the invitation for that show. I decided because it was in the spring and it was near Mother's Day that I would use a photograph of my mother that was very reminiscent of Van Der Zee's photographs that I had shown in the previous exhibition. Norman said, "I only do abstract art. You sent out an invitation that has a photograph that looks like a Van Der Zee. That's not the kind of art that I do and that is in this show. I will take my work out of that exhibition if you send any more of these invitations. Do a different invitation for my work." I understood where he was coming from because he was a dyed-in-the-wool Abstract Expressionist.

The reason why Norman was even in the show is because of Bearden. Norman really didn't want to be in a group show. The way that I knew Romare Bearden was because my father and Bearden were in the Army together, and he introduced me to Romy. It was a great show with Norman Lewis, Romare Bearden, Vivian Browne, William T. Williams, Jack Whitten, Richard Mayhew, Richard Hunt, Philip Pearlstein, Alex Katz, Bob Blackburn, Mel Edwards, Camille Billops, Betty Blayton and Barbara Chase-Riboud. When I was at the Metropolitan Barbara Chase-Riboud wanted me to get the museum to buy her work but Geldzahler wasn't interested. Then I went and asked Betty Parson to see if her gallery would represent her work. Betty Parson liked her work and represented her for a while. When Betty Parson died Jock Truman continued to run the gallery and represented Chase Riboud's work.

Can we get back to the Brooklyn Children's Museum?

The MUSE had a very interesting concept in which they incorporated all of the arts; visual, music, theatre, and dance under one roof. They even had a live young animal zoo in the museum so the kids could come in and play with the animals. It was a totally interactive museum experience. This museum is the oldest children's museum in the United States. The only other one at that time was the Boston Children's Museum. That's were I learned how to fundraise. This museum is run by the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences, which operates the Brooklyn Museum, the Brooklyn Botanical Gardens and the Brooklyn Children's Museum's MUSE. We were trying to raise money to put the main museum in its new location, and try to transition and keep the MUSE as a community based art museum. The people of the community wanted to be on the board. I quickly got into trouble there because I wanted them to be more inclusive of all types of art, and they wanted more of the figurative, naturalistic types of art. They wanted no Pop or abstract art. They also wanted me to hire all sorts of people who were friends and relatives with no backgrounds in art. So, I went back to Betty Blayton again and asked her how to keep all these people in line. She told me to make sure when the bylaws were written that I would have a vote on the board and not just be an employee of the board.

I raised a lot of money and was very good at it. I raised money from the New York State Council for the Arts, the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences and the Brooklyn Borough President's office. I worked with Joan Maynard from Weeksville and both of us got money for our arts organizations. Joan Maynard was an incredible force in making people aware of the importance of black history in the formation of the borough of Brooklyn.

When I left the MUSE, I did an exhibition at my apartment art gallery of Bob Rogers' fashion works. He did high end, one of a kind fashion dresses, shirts and canvas bag accessories. We designed a bag for the Coalition of 100 Black Women and the membership all bought the bag. And for Encore Magazine we did an Encore bag. We did a bag for Essence Magazine and advertised Bob Rogers's canvas bags made to group orders in the magazine. Bob later started making the bags in India so we could get them manufactured cheaper.

I learned this from my father who told me to always have something that brings in money that you could depend on. That's why all of my career, I have always done something that had an entrepreneurial aspect to it.

Now I have a website, www.BurgessFineArts.com. Adger Cowans is in there along with Betty Blayton, Ray Grist and Camille Billops, who are in attendance here today among other artists.

When did you meet Vivian Browne?

I met her at the Art Students League at the Board of Education. She did the kind of art that I liked, which was abstract art. She hired me to teach at Rutgers University, Newark campus, in 1977. I taught the Introduction to World Art History and an independent study for art history majors in nineteenth century art.

African American art is a division of American art, but more importantly it has really grown in terms of moving from figurative, naturalistic depictions, which comes out of our crafts background during slavery. Now most of the artists practice in all of the various genre forms like any other artist. Again, that's why they need to be judged as American artists or artists of the world.

Art is fundamental to our lives. I believe in art, truth, beauty, and in nature. Those are the forces that unite all things together. The eternal recurrence of nature is perhaps the most significant thing that has affected artists and their expressions. Because we get these four seasons every year, after every year, this, more than any other single thing has influenced artists than anything else. Not race, religion, countries of origin, environments or ethnic backgrounds. I think it is that connection to nature that is really the whole ethos of the artist's imagination and need to create.

Would you say that is the concept of nature and spirit?

Yes, because natures depicts the spirit. Nature is spirit. It is the spiritual function of our lives that gives us meaning. It is through nature and the spirit of nature that gives the creative impetus reason to surface and be explained by human creativity.

Can you talk about your venture in the business world?

I was dating a woman who worked for Xerox. She made more than I did, and I was director of the Brooklyn Children's Museum. She asked me to come and work at Xerox. I went down there with no suit or tie on and applied for a job. I was told to come back wearing a suit and tie. I came back to Xerox, got the job. I knocked on every single door in the Empire State Building selling Xerox equipment. My territory was the garment district. They didn't want to use Xerox, so I got them to use facsimiles to see the manufacturing that they were doing in Hong Kong so they wouldn't have to fly there to check the quality of the textile and garments. They would use a Xerox copier and fax machine so they could get a copy image of what they were producing in China. I made quite a bit of money doing that.

From that I decided to deal in office furniture. My father knew someone at Steelcase, the leading manufacturer of office furniture in this country, and I got an interview as a result at their Park Avenue office and got a job as District Manager. I called on the architectural firms, real estate developers and construction companies. In 1980, I ran into two Jewish guys, David and Larry Itkin of Itkin Office Furniture, and an Italian architect, John Varacchi. They owned Furniture Consultants, Inc., the best full service office furniture company in New York City at that time. Prior to that, I was Vice President of Sales and Marketing for the Gunlocke Company. The president of the Gunlocke Company was trying to buy the company from its owner, S & H Green Stamps. He asked me to help him with financial projections and bolstering national sales and that he would help me in going into my own office furniture dealership franchise with Furniture Consultants with if the buyout deal went through. I agreed and did a lot of recruiting around the country and made sure our sales and marketing efforts were up and at levels that were in sync with the business plan.

How many people were working with you?

I had about twenty people working for me. The company was bought, and I started my own office furniture design business in 1982. I went from 1982 to 1990 in that business selling office furniture to major corporations, government agencies and nonprofit organizations. It was from those major corporations that I sold Xerox equipment and office furniture so that I was able to start my current business, an executive search, diversity recruiting, training and human resources management development consulting practice, which I started in 1994. I have gone back to all the companies I have ever worked with for search business and gotten them again as clients due to the relationships I have developed and maintained over the years.

Likewise, I just want to reiterate that Betty Blayton has also been a resource that I have gone to for tapping people for money or either to buy art or support artistic endeavors I have been involved with. And Betty has brought me into the Children's Art Carnival to help with some with fundraising development and benefit events as chairman of the board.

What boards have you been on?

I was Chairman of the Board of the Children's Art Carnival, a member of the board of Feminist Press of the City University of New York. I was on the Board of the Bronx Museum of the Arts. I have been two times Vice President of 100 Black Men's founding chapter here in New York. I was Chairman of the Board of the National Minority Business Council. I worked there with Vera Moore who is President of Vera Moore Cosmetics. We started a Women's Committee which has Annual Conference for women business owners.

I just finished recruiting a chief financial officer for the Dormitory Authority of New York State. I did a CFO for Siemens, the German firm. We found an African American for that job who could speak German. We have done major searches for Philip Morris. When I decided to go into this business, Phillip Morris gave me sixty thousand dollars to recruit people for them.

How I got from furniture to search was the stock crash and downsizing that occurred at the end of the eighties. I realized that the only other industry in New York was people, not manufacturing, and I decided to go into executive search.

We have done international searches in places like Australia and Hong Kong. We do specialized training and development for construction in terms of how to train people to deal with diversity in their office environments. That website is www.TheBurgessGroup.com.

If someone were to come to you looking for a job what would you say specifically to him or her?

We only do mid- to senior-level searches. We are a generalist firm, and we do all industries and disciplines. For two years when the search business was slow (2004 and 2005), I went back to school and got a certificate in commercial real estate and worked as Vice President for CB Richard Ellis, the largest commercial real estate firm in the world in their Wall Street office.

The key to anything is that you have to have an artful way of building and maintaining relationships across all lines in all dimensions and in all fields. When I got out of college I asked my mother what was the most important thing I need to keep in mind going forward in my career, and she said "Your presentation development skills. That is how you stage, present and ask yourself if you have effectively created or stated what you were trying to achieve."

She also told me to follow my scientific method from my science projects. You have a hypothesis; you have to demonstrate some proof, and show how you came up with those ideas and how you have justified them.

Do you have last words on the collecting of art?

Collecting art is crucial. You should look upon it not as just being in possession of one's history but also as an investment. Art is of human and material value and collecting it is important to personal fulfillment. My mission for the next twenty years is to see that more art is appreciated, collected, and bought by all.